Blueberries and How to Encourage Them

by Sandy McCoy

Blueberries, along with loons and white pines, are essential parts of the Pointe au Baril experience. Somewhere in the back of my mind there will forever remain a memory of picking blueberries on hot afternoons, each tiny berry going plink in the can. During the off season, I slip off into memories of blueberry pies and pancakes.

I would like to introduce you to our local blueberry and explain some things about blueberry production (and suggest some ways to increase production).

Some Botany

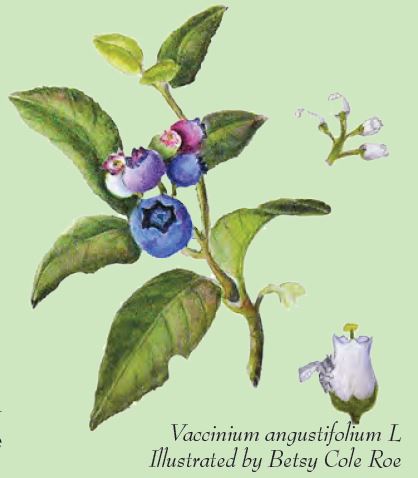

Our blueberry is Vaccinium angustifolium, the “lowbush blueberry.” It is a member of the Heath Family (Ericaceae), along with heather, wintergreen, azaleas, and many other plants.

Its closest relatives are in genus Vaccinium, a widespread group of 450 species that has representatives from the Arctic to the tropics, Old and New Worlds. There are even members of the genus on Madagascar and Hawai’i. Unexpectedly,

cranberries are in genus Vaccinium.

The most similar species to the lowbush blueberry is the velvetleaf blueberry, V. myrtilloides, which is found on Georgian Bay. Velvetleaf blueberries have downy twigs, while lowbush twigs are hairless.

Photo by Wild Blueberry Producers Association of Nova Scotia.

The plants that could be mistaken for lowbush blueberries at Pointe au Baril include black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) and huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata). Drop these names into the internet if you want to see

what they look like.

Lowbush blueberries are part of a group of close relatives within genus Vaccinium, Subgenus Cynococcus. These blueberries bear their flowers and berries at the end of their branches, and not individually at leaves. These are the other North American blueberries, and they number around a dozen species. This subgenus includes the highbush blueberry, V. corymbosum, which was bred with lowbush blueberries to produce the large blueberries in clamshell packages at the supermarket.

The lowbush blueberry is (unsurprisingly) a low shrub. It rarely exceeds 30 centimeters (one foot) in height. Its leaves are oval and pointed, narrow, which gives the plant its specific name, angustifolium. Its twigs are thin and hairless. A\good part of the plant is in underground roots, or stolons, through which a single plant, and a single genetic clone, can spread over large areas.

Blueberries bear bunches of pale white flowers in May and June, each with male and female parts (pistils and stamens). The flowers are shaped like tiny upsidedown urns, and are pollinated by a range of insects, including bumblebees. The

berries come ripe in July and August.

Lowbush blueberries grow in acid woods from Labrador to Manitoba in Canada, across the Upper Midwest, and along the Atlantic Coast and Appalachians as far as the Carolinas. They are ubiquitous in our area.

The berries are eaten by every sensible organism that encounter them. They are particularly important to bears. I know, to my sorrow, that Canada geese like them. Farmed “wild” blueberries in Nova Scotia. We do not see this sort of abundance at Pointe au Baril.

Blueberries as Fruit

One place to look for information on blueberry fruit production is the frozen wild blueberry industry.

This homely little bush is indeed the basis of an industry in Maine, Quebec, and the Maritimes. Commercial growers manage large, naturally occurring blueberry barrens. The fruit that they gather is first frozen and then shipped

worldwide. I have found these frozen, packaged lowbush blueberries, bought in both a Californian and an Australian supermarket and baked, almost indistinguishable from the fruit I gather fresh on our rocky islands.

The word “industry” is not an overstatement. Nova Scotia alone reports annual sales of $70 million dollars. There are 28,000 hectares of blueberry barrens in Québec. The barrens are fertilized, pruned, and irrigated. The berries are, implausibly, harvested by hulking expensive machines, although hand harvesting with specialized rakes is also important.

YouTube shows videos of trucks full of flats of berries being transported to processing facilities, where the berries are sorted mechanically to removed leaves, twigs, and green berries with astonishing accuracy. For a cottage berry harvester, the sight of a large conveyor belt swarming with plump little blueberries is jaw-dropping.

Wild Blueberry “Cultivation”

The blueberry growers have learned a few things about the plants and how to make them produce. The University of Maine Cooperative Extension has extensive materials on management of blueberry barrens, as do Québec and the Maritime Provinces. I have also used New Brunswick’s online materials here.

Pruning happens on a two-year cycle. The plants are cut almost to the ground late in the season, when much of the plants’ nutrition and energy has retreated to the stolons underground. The next year, the plants produce vegetative growth in the form of new branches, and the year after that the new branches produce flowers and then fruit.

Pruning is done by mowers or by fire. Setting fires in the barrens mimics natural cycles and, almost certainly, First Nation practices. Fire destroys many insect pests and molds that can harm the fruit. Fire, however, seems to impoverish the soil. Growers seem to favor mowing, partially because mowing keeps more of the organic matter in place.

The frozen wild blueberry industry wouldn’t be modern without fertilizers. Nitrogen deficiencies result in weak growth and flowering and small fruit size. Over-fertilization produces new branches that are killed by winter freezing.

New Brunswick tells us that “[t]he wild blueberry prefers to get its nitrogen in ammonia form. That is why fertilizers containing nitrates must be avoided. The forms of nitrogen most commonly used are ammonium sulfate (21-0- 0),

monoammonium phosphate (11-52-0), and diammonium phosphate (18-46-0). The last two forms of nitrogen also supply phosphorus.”

Some growers have irrigation systems in place for those years when June and July are dry. A spell of drought will cause the plant to drop their fruit. Wind can affect the bushes, too, by its drying effect, by killing branches in winter, and by interfering with pollination. I think that drought and wind explain variations in

blueberry crops at Pointe au Baril.

Maine mentions simple, acidic mulches as a way of promoting blueberry plant

growth.

Pollination

Pollination is also essential. If pollen does not reach the flower’s stigma, there is no fruit set, and no fruit. Blueberries do not typically self-pollinate, even though the flowers are “perfect,” meaning that both stigma and pistil occurring in a single flower. Pollinators move the pollen from plant to plant.

Bees, typically native bees, including bumblebees, are typical pollinators for blueberries. Growers have both brought in honeybee hives and encouraged native bees by leaving natural areas scattered around the blueberry barrens for native

pollinators.

What to do at the Cottage

My suggestions to improve blueberry production are weeding, pruning, and mulching. Other useful steps might be fertilization and watering, but those are more challenging at the cottage. Because there is plenty of habitat for wild bees at the cottage, pollination is probably not an issue.

The University of Maine Agricultural Extension website list the top ways to improve blueberry plant health as being “Fill Bare Spots (mulching); Fertilize, Synthetic Nutrients; Weed Reduction.” Weeding is the easiest. Simply cut or pull the plants competing with your blueberry patch. This can be done at any time of the year. Mulching means applying wood chips, bark, or pine needles to areas where the cover over the rhizomes or stolons of the plants is thin. This is done to fill in patches in blueberry barrens. On our islands, the plants will certainly welcome more organic matter to grow in.

The goal of pruning is to encourage vegetative growth that in the second year produces flowers and berries. It’s best done in late fall, which is when commercial growers do it.

I would therefore suggest a selective pruning of old and unproductive branches in your patch. If you are only at the cottage during the summer, I think that pruning is still appropriate. Personally, I would be conservative and remove only at most a quarter of branches a year, particularly if cutting happens in summer. Standard pruning of shrubs involves removing a third of branches to encourage growth.

Water a blueberry patch after a couple of weeks of drought, before or after harvest.

Finally, fertilizer needs to be applied very carefully and sparingly. It’s just one factor among several. Excess fertilizer will produce growth that can be killed during the winter. New Brunswick recommends applying fertilizer very lightly early in spring and then again after harvest of the fruit.

You also don’t want chemical fertilizers draining off into Georgian Bay. Remember that island soils are very thin.

Azalea and rhododendron fertilizer, in small amounts, is probably appropriate. The University of Maine suggests some “new” and less “chemical” methods, namely urea (dried chicken manure), compost, and foliar spray. For more information, including information on more “traditional” chemical fertilizers, visit https://extension.umaine.edu/ blueberries/factsheets/nutrient-management/.

A common piece of advice on the internet is to apply coffee grounds to blueberries. The theory is that the grounds are acidic and provide nutrients. However, I would compost the grounds first because caffeine may stunt plants.

I reached out to Delaina Arnold of the Georgian Bay Biosphere for this piece. Delaina is skeptical about imposing industrial techniques on our landscape, a point I agree with. Delaina works in education and community gardens. She

would “avoid the term fertilizer all together” and only use compost. She asked if I could also mention “that, by and large, wild plants don’t require our assistance, and a reminder that we should only ever harvest a portion of a wild crop, leaving the remainder for the land and wildlife.”

Final Thoughts

A whole separate article could be written on cooking with blueberries. Several more articles could be produced on their ecology and traditional uses. All this information shrinks to insignificance when compared to a dish of blueberry

crumble on a summer evening. Many thanks to Delaina Arnold of the Georgian Bay Biosphere for help with this article.

Blueberry illustration by Julia Beery, 2021

Blueberry bush illustration by Betsy Cole Roe