by Trudy Irvine, Member Education Committee

Tennis players at the Club were treated to the sight of an enormous Eastern Fox Snake sunning itself along the shoulder height horizontal bar of the Court 1 enclosure on Sunday morning. Obviously, an enthusiast of the game, the snake had its long body twined through a few of the vertical chain links, coolly watching the less than Wimbledon level tennis happening on Courts 1 and 2. All he/she needed was a little white hat.

The sight of a creature with no arms or legs climbing many times its body length, propelling itself forward in a straight line with no visible effort, or even jumping several feet can be a little…disconcerting… but is certainly something to marvel at. Snakes get their agility from powerful, finely tuned muscles attached to their vertebrae (which number anywhere from 141 to 435, compared to our 33), and several kinds of specialized scales on their bodies. (For a video of fox snakes and to learn more about them, click on the picture of the fox snake below for facts about them and how to distinguish them from other varieties, including rattlesnakes!)

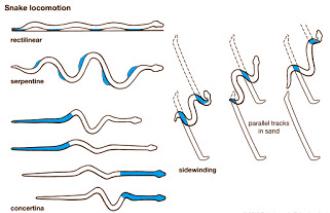

Snakes move using combinations of four different kinds of locomotion. For climbing or moving in tight spaces, they use a motion called concertina movement. They extend the front part of their body along the surface and use their specialized rectangular ventral/belly scales towards their tails to grip the surface and support the back part of their bodies. After extending their heads, they then alternate that “grip” of the ventral scales to the front of their bodies as they draw their tails along.

Serpentine movement is created with a series of muscular contractions creating horizontal waves from head to tail, where the sideways force propels the snake forward. We see snakes swimming in this fashion.

When a snake is stalking prey or moving about in a leisurely manner, it makes use of rectilinear movement – muscles draw the skin of the belly forward, causing the scales to bunch up. Other muscles then contract and force the rear edges of the bunched-up scales to dig into the ground, allowing the snake to pull itself forward. Waves of contraction and relaxation travel down the snake’s body as it continues to move forward in a straight line with seemingly little effort.

Sidewinding movement is something we don’t see in Ontario snakes- where a sideways movement is initiated in the middle of the snake’s body- creating a wave that helps the snake travel like a skipping rope over smooth surfaces such as sand.

The next time you cross paths with a snake perhaps you can (after the initial surprise of such an encounter) admire their skills of legless locomotion. For a good video of a fox snake climbing a tree, visit the Georgian Bay Land Trust’s Facebook page or click on the picture to the right from the video.